The Trip

Matsuo Basho reveals to his disciple Kyori that he and his neighbor Kawai Sora are planning a trip. The trip that would make Basho famous.

How wonderful!

Matsuo Basho, Spring 1689

This year, this Spring

As I journey under the sky (Sora)

I おもしろや ことしの春も 旅のそら

omoshiro ya / kotoshi no Itam mo / tabi no sora

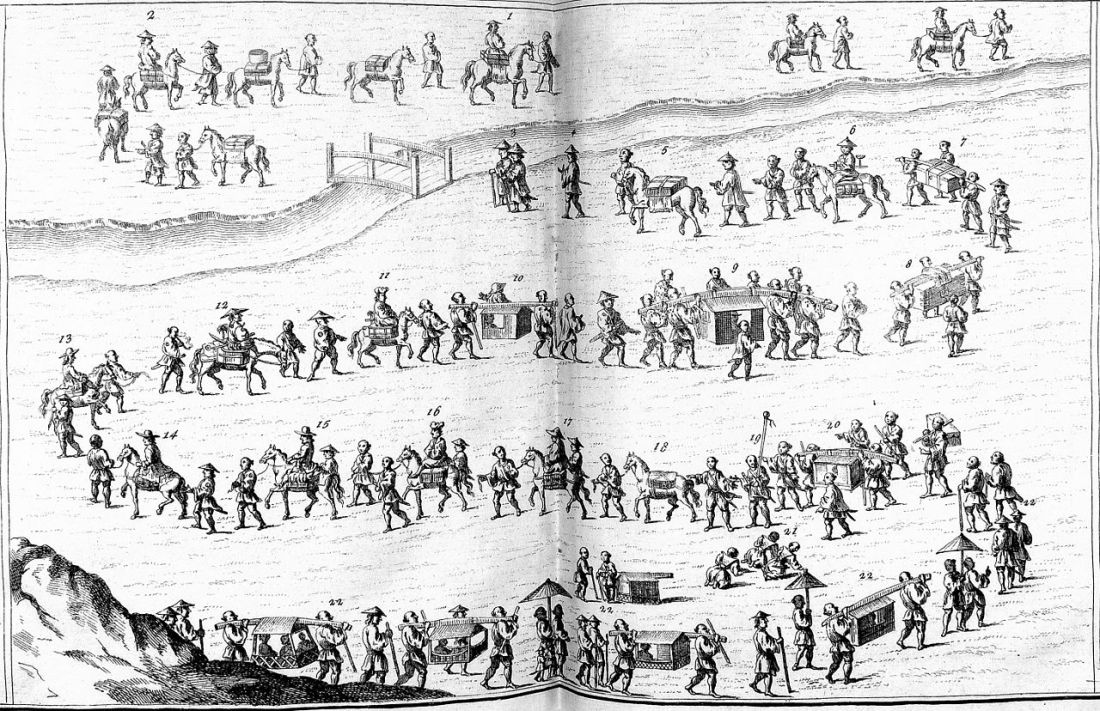

The trip was to become Oku no Hosomichi, a nine month journey into Japan’s Northern Interior. The notes and haiku Basho wrote along the way would not be published until eight years after Basho’ death in 1694. It would in time make his name immortal.

According to a disciple of Basho, Mukai Kyori (向井 去来, 1651–1704), this haiku was written as a way of saying he was going on a trip with his neighbor Sora, whose name means “sky.” After Basho’s death in 1694, Kyori published stories about his master.

Here is one example of Kyori’s haiku. The smartweed suggest Kyori had health issues (like Basho) and the firefly emphasizes the fleeting nature of life.

草の戸に我は蓼くふほたる哉

kusa no to ni ware wa tade kuu hotaru kanain a dreary hut of wood and grass,

Mukai Kyori, 向井 去来, 1651–1704

feeding on smartweeds am I

— a firefly!

[kusa no to ni (in a thatched roof hut) ware wa (I am) tade kuu (eating smartweed) hotaru (firefly) kana (used for emphasis)] The mention of Smartweed suggest that Kyori like Basho had health issues. Smartweed can be found in wet marshland. It is an herbal medicine taken to stop bleeding from hemorrhoids.

Source of Kyori’s haiku: World Haiku Review

Presumably, Kyori had in mind this Basho’s haiku written about leaving his cottage. It begins with the same three characters 草の戸, kusa no to. Basho cottage is being taken by a family with young girls. Presumably, written on the third of March, Doll’s Day, celebrated in Japan as Hinamatsuri 雛祭り.

in my simple cottage

will come a world of change

full of dolls草の戸も住替はる代ぞひなの家

Matsuo Basho, March 3, 1689

kusa no to mo . sumi kawaru yo zo . hina no ie